Finis Africae: A Foray to Forbidden Knowledge

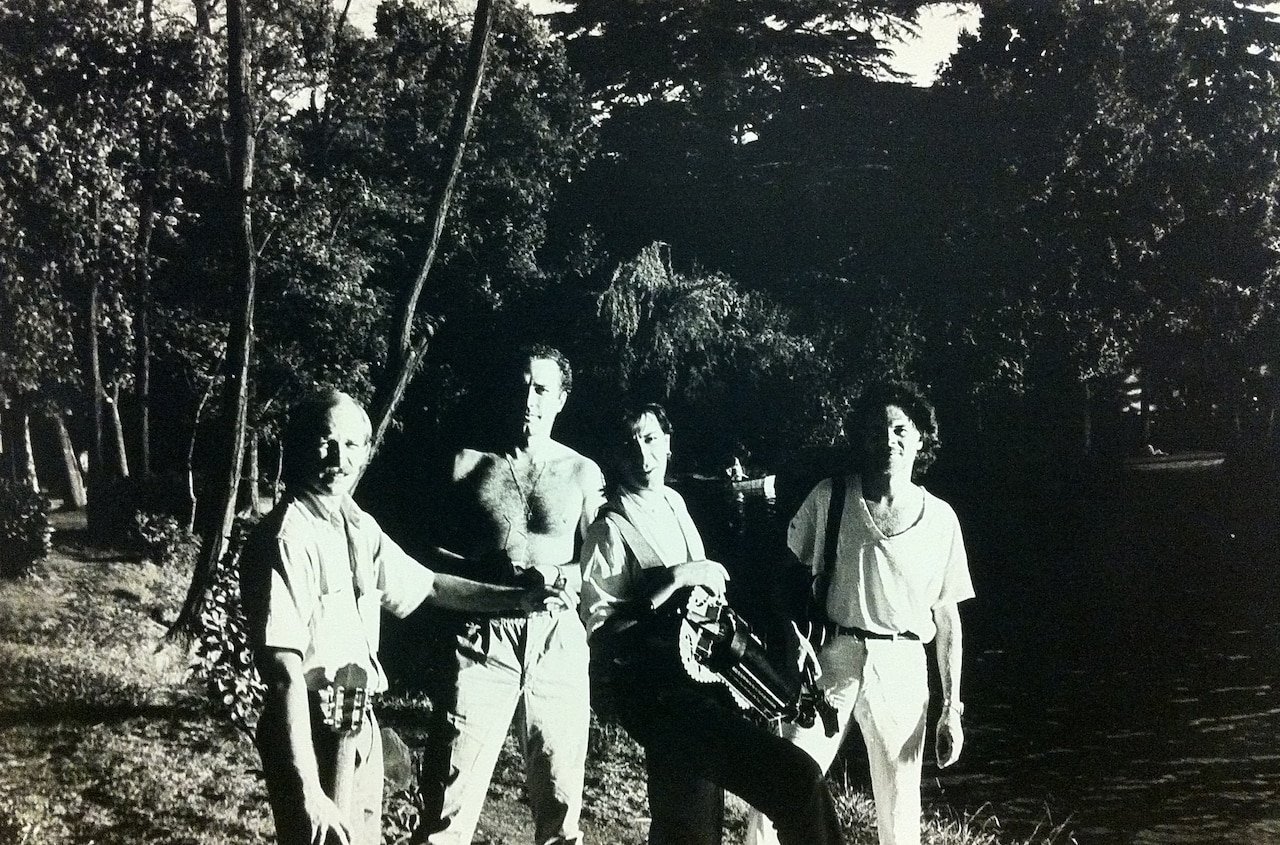

Finis Africae. Photo credit: Luis Delgado

There exists a room — mysterious yet apparent, concrete yet unknowable — in the recesses of some distant fantasy. Obscured in the twists and turns of a labyrinthine library, accessible only to the librarian himself, sits an unaccounted lot, concealed by an aged mirror. Its existence is implied, its contents are unclear, and the name afforded to it — finis africae, or ‘the end of Africa’ — speaks to the cunningly hidden, much-forbidden knowledge that sits within.

The monastery, the aedificium and finis africae are hemmed by the four corners of the paperback, all contrived by Umberto Eco in his first novel, The Name of The Rose. A 14th-century theological murder mystery doesn’t really sound like a surefire hit, but Eco’s debut quickly became one of the best-selling books ever published. At some point in the early 1980s, a copy ended up in the hands of Spanish musician Juan Alberto Arteche.

A young artist raised in Francoist Spain, Arteche’s first musical success came in folk-rock group Nuestro Pequeño Mundo. Founded in 1968, that eight-strong rock outfit fused contemporary musical modes with Spanish folk traditions, taking to national television with their arrangements of popular such as “The Drunken Sailor,” “Me Caso, Me Madre,” and “I Will Never Marry.” Guitarist first and vocalist second, Arteche took the lead in the group’s rendition of “Sinnerman,” included on their debut record, El Folklore De Nuestro Pequeño Mundo.

Nuestro Pequeño Mundo released eight records over their 14 years, roster changing and sound evolving as they moved into the late ‘70s. Juan Alberto Arteche was a mainstay, taking on arranging responsibilities on traditional songs like “Tanto Vestido Blanco”; sea shanties such as “Santy Anno”; gospel classics such as “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho;” and Irish staples like “Whisky En La Jarra.” By 1980’s Te Añoro, the group was performing original songs, incorporating more instrumentation and taking on a stronger Spanish influence, but by the close of 1982, Nuestro Pequeño Mundo was no more.

Arteche and his bandmates emerged to a new Spain. The death of Franco in 1975 began a slow transition to democracy, and at the start of the ‘80s, countercultural movements like Madrid’s La Movida Madrileña and Vigo’s Movida Viguesa helped usher in a new wave of creative expression. The post-Franco counterculture spawned new sounds, new styles, and even languages of their own, and that atmosphere — vibrant, messy, bold — was contagious.

“I was in the mood to experiment with other ways to compose and play music,” remembered Arteche in the liner notes of 2013 compilation Finis Africae – A Last Discovery. He formed a new band, Finis Africae, alongside fellow experimentalists Luis Delgado and Javier Bergia, whom Arteche had met through the burgeoning Madrid music scene. He appeared alongside Delgado on Babia’s Oriente, a 1982 record that both galvanised his intrepid urges. Invigorated by new technologies, the trio eventually began crafting remarkably free soundscapes together.

The post-Franco freedom of the early ‘80s coincided with a boom in recording technologies, and the trio made use of the newest consumer innovations, in particular the then-revolutionary Tascam four-track cassette recorders. Tracks were laid patiently at home and mixed expertly in professional studios, striking a balance between homebound perfectionism and studio-quality sound.

Their debut LP goes by two names: the simple, self-titled Finis Africae, and the illuminating Prima Travesia, or First Crossing. The latter speaks to the wide scope of the group’s mission, their traversing spirit and cosmopolitan approach entrenched in the unusual sounds within. Arteche plays a wide array of international instruments, including the adufe, a traditional Moorish tambourine; the flute, credited as the aulos, an ancient Greek wind instrument; the bombo, a type of Latin American bass drum; the cuatro, a four-string guitar-like instrument from Latin America; and the sitar, a subcontinental lute. Delgado plays, among other instruments, the hurdy-gurdy, and Bergia makes use of the lute-like oud, the Indian tabla drums, and the plucked Iranian tar.

“Radio Tarifa,” a cacophony of loose horns and scattered percussion anchored by a sturdy bass. A slow build of clanging ambience unravels into distant chants and primal yells, channeling new wave foundations into eclectic internationalism. “The idea was to start a fusion band close to folk timbres and with no boundaries, no ‘finis,’ taking Africa as the starting point,” said Bergia in a 2015 interview with Red Bull, “Africa and the Mediterranean in general.”

The locale of Tarifa, then, is no coincidence: the southernmost point of not only Spain but continental Europe, the Spanish port sits lower than African cities such as Algiers and Tunis. “Radio Tarifa” is an ideal amalgamation, a close connection between both their own identities and the boundless sounds that lay across the Strait of Gibraltar.

“El secreto de las 12,” a seven-minute soundscape, has become a favourite of the kicked-back Baeleric sound. It’s not hard to tell why: the delicate, wind-borne guitar carries a snaking flute through the wilderness, conjuring an idle drift down some Amazonian tributary, mysterious and picturesque. The shorter, denser “Luna” feels like diving into the whitewater, floating peacefully in the depths, and emerging to friendly birdsong from the shore.

“Zoo Zulú” melds funky new-wave guitar lines with languid chants, where the fleeting “Juana y Rosalía” pairs intricate chimes with a sparse bass. It’s “Hybla” that best distills the dreamlike haze of Finis Africae, the mix-and-match fusions emanating like a slow-drifting fog. The melodic vocal is layered atop another indistinct chant, the constant rumble a mystical bedrock on which rock, folk and world modes are juxtaposed.

If any track flaunts these fundamentals, it’s “Managua,” the closest the record comes to a conventional instrumental rock arrangement. Taking a trans-Atlantic trip to the capital of Nicaragua, the post-punk tenets still incorporate some incomprehensible baby talk and an ebbing choir, and the song doesn’t travel toward any grand conclusion. A few pretty chords buoy some precious passages, and once they’re done, things slowly fade into the distance.

On “Bahia de los genoveses,” the closer, things amble back to the Mediterranean. The “bay of the Genovese” likely refers to Catalan Bay, a Genovese fishing village that sits in the shadow of the Rock of Gibraltar. A delicate evocation of that once-serene fishing village, the phasing strings and whispering woodwind channel a peaceful aimlessness. The sounds beg reflection, the capacity for contemplation unimpeded by melody or mission. Finis Africae close their First Crossing on those sandy shores, striking a meditative mood just a short trip from Tarifa.

Finis Africae, photo by Luis Delgado

Their sophomore effort, 1985’s Un día en el parque, or A Day in The Park, was billed as a 2ª Expedición. “I had spent many years walking under the statues, playing football and ‘rescuing’ or falling in love with pretty girls,” said Arteche in the Red Bull interview, explaining the inspiration gleaned from his walks through Parque del Retiro in Madrid.

The opener — a brisk twenty-second vignette titled “Entrando En El Jardin,” or “Entering The Garden” — centres an impassioned streetside performance, growing nearer before receding as we step past the artist and through the gates to the park. A wave of serenity bursts forth on “Los Pobres Del Mundo Tocan El Bombo,” or “The Poor of the World Play the Bass Drum,” and a bubbling stream courses throughout “Pipo Y Las Libelulas,” or “Pipo and the Dragonflies,” taut strings and phasing synths conjuring otherworldly tension.

Where Prima Travesia was just that, a wandering cross-continental odyssey, Un dia en el parque cast an intrepid gaze over sunny days in sprawling suburban parks. Crowds collide with glimpses of green, with beauty breaking through in both nature and humanity. There are splashes of wonder in the everyday, such as on “Triciclos En La Chopera,” or “Tricycles in La Chopera,” a nod to the locals of that Madrid ward.

“Ceremonia Magica En El Estanque,” or “Magic Ceremony in the Pond,” speaks to two of Retiro Park’s pleasures: the everyday magic found in nature, such as the dragonbflies that buzz atop the rippling waters, and the street performers that line the ponds and lakes throughout the park, performing tricks flanked by the towering Alfonso XII monument. The looping, disorienting “Salida Del Parque,” or “Park Exit,” pulls us from the trance of our leisurely stroll, the winking inclusion of a street band performing “Ob La Di, Ob La Da” a clear end to the suspended serenity of parklife — “ah, life goes on!”

The foundational trio behind Finis Africae burned bright and fast, splitting after that sophomore effort, but the creative rapport that underpinned Africae carried into the trio’s solo endeavors.

Javier Bergia’s Recoletos, released the same year as Un día en el parque, featured photography from Arteche and bass from Delgado. The duo formed another outfit, Ishinohana, and soon released 1986’s La Flor De Piedra. In the wake of their band work, Bergia and Delgado continued to work closely, with Delgado contributing to Bergia’s 1988 record La Alegría Del Coyote, producing and playing on his 1989 LP Tagomago, and reuniting with Arteche on Bergia’s ‘90s output.

Arteche continued as Finis Africae, releasing the sprawling, tropical Amazonia in 1990. A tighter emphasis on the Amazon leaves plenty of room for ambient experimentation, with Arteche and his band patiently evoking the thick brush and damp canopies with little concern for structure. The group’s subsequent output, such as 1995’s Campos De Sol Y Luna, 1999’s El Viento Que Mece Los Juncos, and 2001’s Retales Y Apuntes, remain rarities, a scant few tracks appearing on 2013 compilation A Last Discovery: The Essential Collection, 1984-2001.

That collection did much to shine a light on Finis Africae’s catalogue, prompting the reverent retrospectives which first introduced me to the group so many years ago. In that time, amongst all the strikes and gutters, the ambient new age of Finis Africae has continued to resonate. There was a stretch where a globetrotting instrumental adventure was the closest we could get to foreign shores, and others where peace of mind proved just as elusive as international travel.

You’ll find a surprising amount in both Prima Travesia and Un día en el parque, buoyed by the bold collisions throughout. It’s simple yet daring, the soundtrack to a sunny afternoon, and a testament to the power of that titular ‘forbidden knowledge’; pushing past the boundaries that hem us in and fusing sounds and styles yet synthesized.