Fishmans Friend

In the decades since their dissolution, Japanese dub band Fishmans have amassed a cult-like following. As one of the cult’s latest victims, I’m diving into the sublime beauty of the group, tracking through their brief career, and considering what makes their art so timeless.

Gather ‘round, ye salty dogs, and hear the tale of workplace banality, dreamy humanity, and a saving grace.

I was a fan of Fishmans, as much as one is a fan of any band with which they’re passingly familiar. I knew “BABY BLUE” and “Nightcruising,” and I’d given “Long Season” a few spins, but they were an algorithmic detour; the kind of thing my phone might throw up every now and then.

On a Wednesday, lost in an accounts binder, I needed direction only good music can provide. I threw on some Fishmans, plugged my ailing phone to the mains, and perched it on the edge of the piano. There it sat, just beyond my reach, as I sunk into a work-induced fugue state. The patient wandering of “Long Season” lulled me into serene productivity, but 35 minutes on, with many markers still to adhere, it ticked over. A few feet from my grip, I let it roll, and so begun my Fishmans phase.

Enchanting and diffuse, Fishmans wield a multifaceted charm. It’s in the dreamy atmosphere of their best work, the late Setagaya trilogy, but also in their strange genre fusions, harking back to their reggae beginnings and alt-rock detours. The pronounced basslines and crisp drumbeats frequently demand attention, a real achievement when taken along their alien vocals. There’s something to be said for the language barrier, too: as with groups like Sigur Ros and Yellow Magic Orchestra, they’ve beguiling lyrics, so foreign as to work like another melodic instrument.

These qualities have helped Fishmans find a fierce online fanbase, but in their ‘90s heyday, those same hallmarks kept the group underground. Their gradual renaissance owes much to many, but it helps that, in the eyes of their devotees, Fishmans have more than just a brilliant string of singular records: they have a story. It’s part-tragedy, part-triumph, but all-compelling.

My Fishmans take begun at my living room table, but the Fishmans tale itself picks up in a booming Tokyo. In the heart of the city, bordering the famed Shibuya ward, sits the special ward of Minato. A hotspot of offices, consulates and universities abutting Tokyo Harbour, it seems a hub of business and academia — and maybe not the sort of place you’d find a flourishing reggae scene. In the wake of 1980’s Pecker Power and Instant Rasta, Japan was embracing reggae, dub, ska and rocksteady like never before.

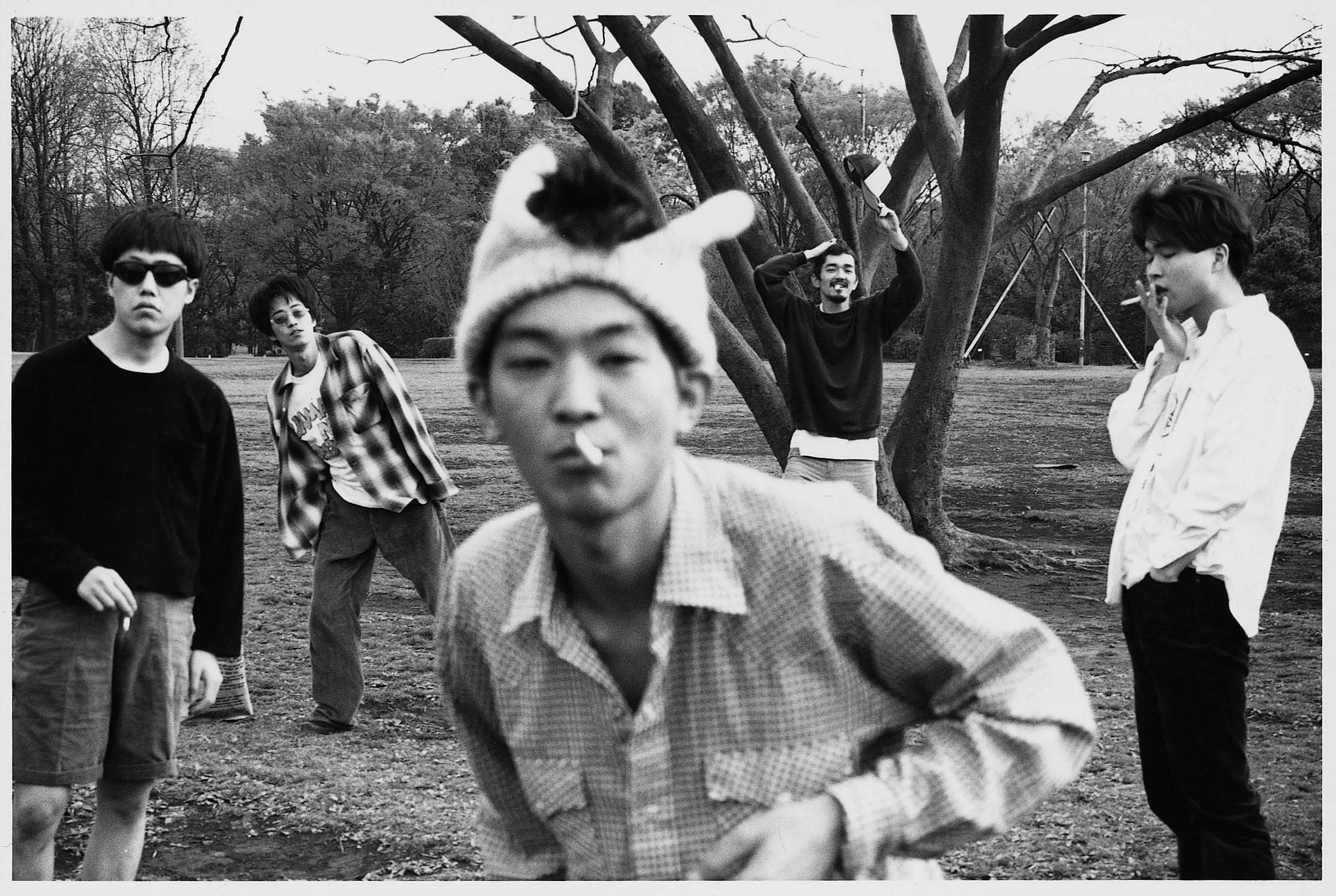

Fishmans quietly formed in mid-1987, then comprising Shinji Sato, Kin-Ichi Motegi, and Kensuke Ojima. Sato sung lead, Motegi drummed, and Ojima played guitar, first on their unreleased demo tape, and then in small clubs throughout Tokyo. They found a bassist in Yuzuru Kashiwabara and made their debut on 1989’s Panic Paradise, a compliation spotlighting emerging pop-punk, ska and reggae groups.

The quartet found their fifth man in keyboardist Hakase-Sun, who joined in 1990, and soon stumbled upon a powerful collaborator in Kazufumi Kodama, trumpeter and founder of trailblazing Japanese dub outfit Mute Beat. A veteran of a prior musical generation, Kodama’s influence earned the band a deal with Virgin Japan and brought a light pop-reggae flavour to their debut, Chappie, Don’t Cry. It’s a straightforward anomaly in Fishmans’ catalogue, but their cheery contagion and endearing innocence bursts through on cuts like ”Good Morning,” “Hikouki” and “Chance.”

That innocence — buoyed by Sato’s otherworldly vocals — is a throughline for the group, who spent years searching for their signature sound. Their sophomore album, King Master George, abandons the reggae roots of Kodama for the scattershot of Haruo Kubota. The experience was apparently frustrating, and the results are mixed. King Master George careens from style to style, with bold new ground and familiar territory abutting. Peaks like “Nantenetto” and “100mm Chotto no” are the first glimpses of Fishmans’ dreamlike psychedelia, whilst moments such as “Tayonari Tenshi” and “Doyoubi no Yoru” recall their debut.

True to its title, Neo Yankees’ Holiday, the group’s third LP, landed as a pleasant detour. A sunny disposition pervades, the restless experimentation of King Master George replaced with a sharpening vision of Fishmans psychedelia. That coherence came from a new emphasis on dub — an instrumental, electronic offshoot of reggae — which bridged the spacey textures of “Ikareta Baby,” the odd segues of “Smiling Days, Sunny Holiday,” and the sample-heavy cavalcade of “1, 2, 3, 4.”

If Fishmans hadn’t quite arrived at their golden years, they’d taken a sure step forward, thanks in part to producer ZAK. Their third producer in as many albums, his quirky vision coursed throughout Neo Yankees’ Holiday, though the oddities subsided some on successor Orange, the alt-rock prelude to the group’s strongest run. Arguably Fishmans’ most accessible album, Orange drifts from a rock-heavy open to a largely laidback b-side.

Kensuke Ojima left the group in 1994, and though he was momentarily replaced by Sugar Yoshinaga of Buffalo Daughter, she didn’t appear on the record’s striking cover. Her guitar played a central role on Orange, which opens with the rollicking “Kibun” and drifts to standout hit “Wasurechau Hitotoki.” Single “My Life” remains one of the outfits’ best Shibuya-kei outings, the cheery resignation of the track carrying a likeminded tagline: “life is a sexually transmitted disease.” Elsewhere, “Kansha (Odoroki)” is a blistering display of Fishmans’ totality: Kashiwabara’s nimble basslines dance under Hakase’s searing keys, with Motegi’s blistering drums and Yoshinaga’s funky guitar punctuating Sato’s pure vocal melodies. The synergy is palpable, but the genre itself an odd detour. It wasn’t until 1996’s Kuchu Camp that everything really came together.

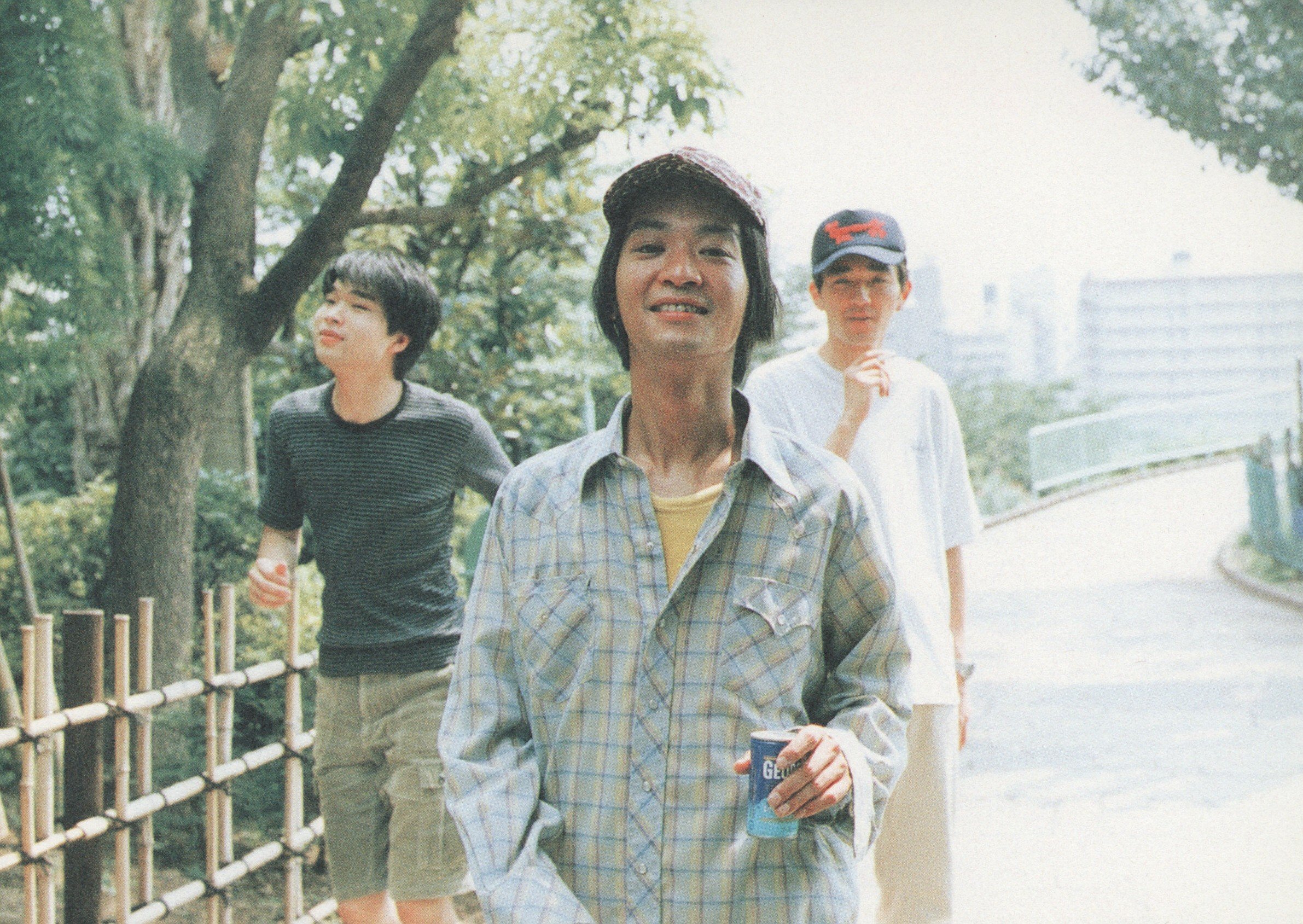

Following Orange, Fishmans were whittled down to three. Hakase-Sun left the band soon after Kensuke, and in 1995, the slimmed group left Japanese label Media Remoras and signed with storied international powerhouse Polydor. The contract demanded three records in two years, but in return, the trio were supplied with a recently-renovated two-story studio. Christened Waikiki Beach, the Tokyo base would provide Fishmans with a newfound stability, facilitating the bold strides of their final three records — the since-legendary ‘Setagaya Trilogy.’

On Kuchu Camp, the first of that trilogy, Sato’s intoxicating treble found a home within a pronounced dream pop edge, perhaps seen nowhere better than standout cut “NIGHTCRUISING.” The bouncy standout cut, “BABY BLUE,” pairs a familiar dub within the record’s tight aesthetic, and “SUNNY BLUE” sees the trio shift into trip-hop. The tracks skew long, indulging hazy arrangements and breezy instrumental loops, though none could possibly presage their subsequent LP, Long Season.

The second instalment of the Setagaya Trilogy, Long Season arrived nearly nine months after Kuchu Camp. A thirty-five minute expansion of standalone single Season, the five-part variation on a theme unfurls with patience, a longform story on a slow climb to the crescendo. Sato’s vocals, sparse and subsumed by instrumentation and effects, plays on a simple conceit:

“Driving from one end of Tokyo to the other, halfway dreaming...”

Motifs rise and fall, pianos and electric guitars giving way to wordless vocals and hypnotic repetition. There’s a large sound collage at the centre, an avant-garde mix of drips, chimes, and synth effects. It’s an oasis of intrigue, a striking moment that pushes beyond Fishmans’ usual proclivities, fostering a strangely magical atmosphere. “Long Season” is a true journey, one that sees the listener off and welcomes them back in vastly different states. It’s an easy experience to surrender to, mighty and moving.

Far from the uniform recording it seems, “Long Season” was pieced together by ZAK from a smattering of laidback sessions. That atmosphere wouldn’t last, and the group’s final record, Uchū Nippon Setagaya, was plagued with a tension from which the group would never fully recover. In one telling, Sato’s vision was becoming too strong, with demos coming in so fully formed — or so intricately composed — that band collaboration was at best unnecessary and at worst counterproductive.

Tour stress, label obligations and creative strife didn’t show through in the music, with Uchū Nippon Setagaya the peak of Fishmans’ idiosyncratic sound. The nearly nine-minute “WEATHER REPORT” charts a slow climb from sparse beats to wailing guitars, all but Sato’s vocal muffled beneath a dreamy veneer. The melancholic dream-pop “IN THE FLIGHT” is chased by the eccentric dub flavour of “MAGIC LOVE,” and the record closes out with a powerful one-two: the 12-minute downtempo fantasy of “WALKING IN THE RHYTHM” and the bittersweet hypnogogic rock of “DAYDREAM.”

That track was the last recorded for the album. It was the final song recorded at Waikiki Beach, which closed just weeks after the release of Uchū Nippon Setagaya concluded Fishmans’ Polydor deal. Their rapport having changed, it seemed as though it might be the end. The trio released a 13-minute single, “Yurameki In The Air,” and a second studio live record, The Current Situation in August, but Kashiwabara, still creatively frustrated, soon took his leave. The trio hit the road one last time, wrapping up with their legendary final show at Akasaka Blitz. Billed as Kashiwabara’s final show, it instead proved to be Sato’s farewell — he died of heart failure less than three months later, aged just 33.

The sudden death of Shinji Sato spelled the end of Fishmans. Memorial concerts, brief revivals, spinoff bands and tribute records followed — including the release of one of Sato’s final compositions, “A Piece of Future” — but Kashiwabara and Motegi never reformed the group.

Their final effort, 98.12.28 Otokotachi no Wakare, showed Fishmans at the peak of their powers. A refined recording of their ultimate Akasaka show, it feels as fresh and powerful as any performance ever put to tape, underwritten by a deep rapport and unsullied by pressure. That it remains their defining document is no surprise, given the peerless musicianship and tragic tale that surrounds it. That it’s become a legendarily loved cult record, beloved by both aficionados and music fans the world over, would surprise even the most ardent Fishmans fanatic.

In 2004, artists such as Bonobos, OOIOO and Cassette Con-Los contributed to tribute record Sweet Dreams for Fishmans. The project spoke to Fishmans’ respected place in the Japanese music scene, but a broader international recognition was still elusive. It wasn’t until years later, buoyed by the transformative power of the internet, that the group started to inspire a fervent fanbase abroad.

It’s hard to say just how it started, but sometime in the late 2000s, users on 4chan’s /mu/ started raving about Kuchu Camp, Long Season and, subsequently, 98.12.28 Otokotachi no Wakare. Their clamouring spread to RateYourMusic, where Long Season stands as the 37th highest-rated album. 98.12.28 Otokotachi no Wakare) sits at 44th, the only live record in the top 100. This proves nothing but the relevance of Fishmans to a particular kind of music geek, but it brings their online resurgence into perspective.

In their time, Fishmans were a relatively small-time group. They skirted mainstream success in their home country, eschewed it entirely abroad, and worked laboriously under an intense label deal. The trio toured relentlessly, but never ventured outside Japan. In 2022, it’s not hard to imagine Sato, Kashiwabara and Motegi pulling modest world tours from their string of exceptional ‘90s records. That’s to their credit, but there’s a melancholy in that belated recognition: for most of us, the Fishmans journey was over long before we’d even set out on it.

That Fishmans continues to excite speaks to their distinctive approach and odd inclinations. They’re whimsical but never twee, exploratory but never over-indulgent, unencumbered by the tides of style. It’s a timeless sound that continues to inspire fanzines and fuel exhaustive Wikis, recently bringing forth an impressively in-depth documentary. The Fishmans Movie is a three-hour affair loaded with first-person accounts and rich archival footage, brimming with an appreciation it shares with the devoted audience it serves. Fans fawn in their reviews — reading their passionate reams, you’d think there’s nothing else like it.

In Fishmans’ idiosyncratic style is something unreplicable. It’s easy to put the emphasis on Sato’s striking voice, but Kashwabara’s bass and Motegi’s kit excel in spotlight and shadow alike. You can listen to the most dynamic Fishmans songs in three ways — by vocal, by bass, or by kit — and lose yourself in the minutiae of each. Each component stands alone, yet they elevate each other in their solitary excellence. If a supergroup is a team of champions, then Fishmans are a supergroup of a different kind: a champion team.

All that’s to say, maybe this Fishmans phase isn’t. The speed with which they’ve risen to a favourite, the passion with which I put everyone on, the wistful mood with which I float, headphones on and music blaring… this enthusiasm, like Fishmans’ vision, might just be here to stay.