Automatic Transmission

Throughout the 1990s, Thom Yorke’s anxieties graced some of the era’s best rock music, and few things stoked as much panic in him as the simple automobile. Radiohead’s magnum opus, 1997’s OK Computer, remains the ultimate testament to — and final exorcism of — his enduring fear of transit.

Radiohead have made much of anxiety.

In the hands of the British five-piece, that modern malady turns from symptom to shorthand; a sturdy thread that weaves throughout their ever-evolving art. It’s the tether that ties the disavowed “Creep” to all that followed, from the malevolence of “Street Spirit (Fade Out)” to the chaos of “Paranoid Android,” the doomsaying apocalypse of “Idioteque,” the righteous political anger of “2 + 2 = 5,” the 5/4 freakout of “15 Step,” and the “low flying panic attack” of “Burn The Witch.” In this broad catalogue, spanning from brash adolescence to weary adulthood, few images have proved a sharper vehicle for this anxiety than the humble car.

Yorke’s fixation with motors, all but exorcised by the turn of the century, carried through their formative decade. It persisted like little else, matching the contours of their greater social angsts and evolving alongside the band’s own perspective. Sparked by a near-death accident in the years before the band, his growing fear was further informed by years spent on the road. Ferried about from gig to gig in the innocuous death traps, cars became more than just an image of death — they symbolized a very particular kind of modern life.

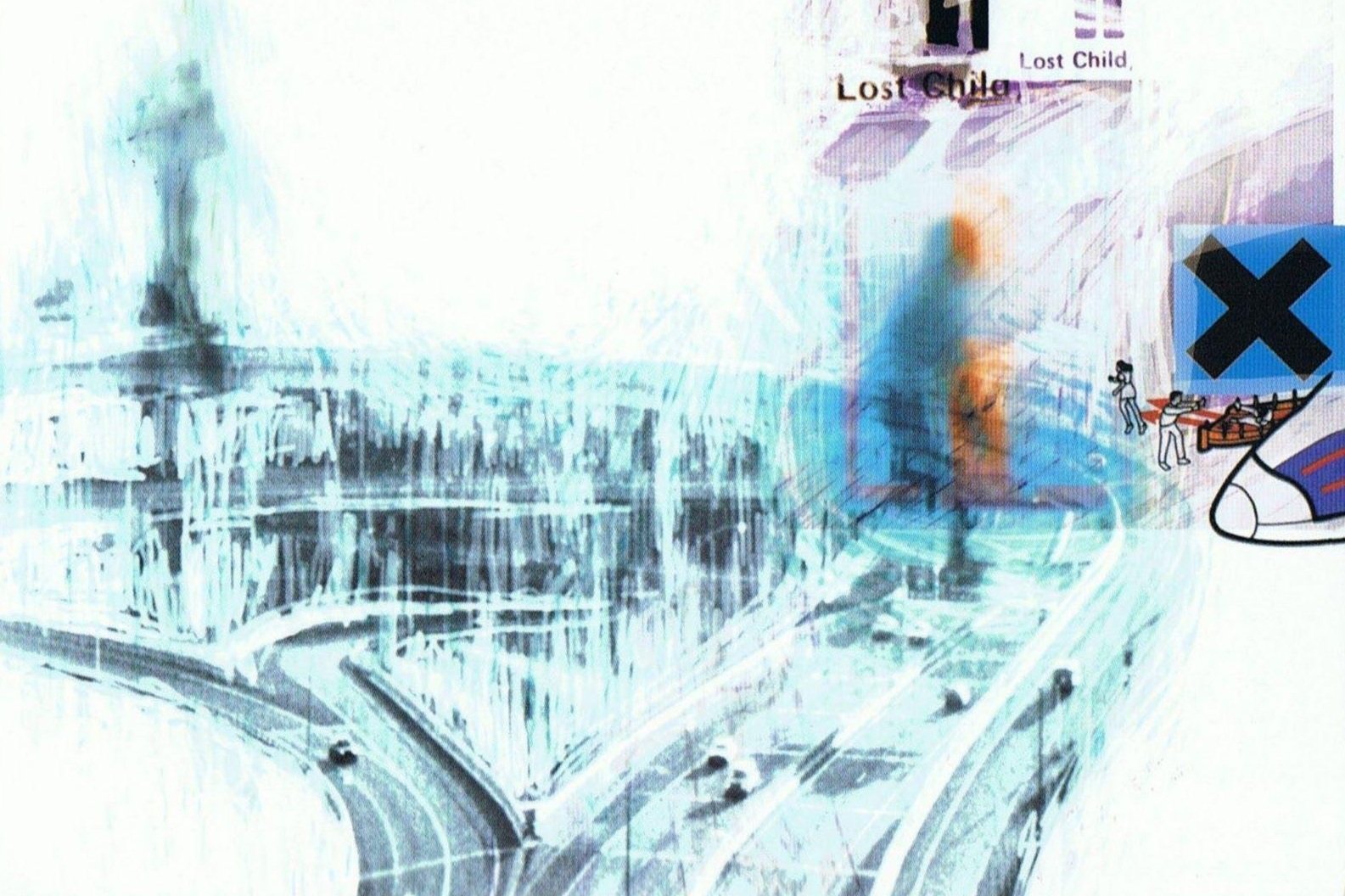

That life, dissected and deplored on the watershed OK Computer, is often seen as a broad indictment of technology. There’s a truth to that, but OK Computer is best understood through the simple car, a fusion of the commonplace and the exceptionally dangerous. That transit is the central theme should not surprise: the album art is adorned with highways, cars, and deplaning diagrams, and the lyrics fix around mechanical movement, speed, and a punishing pace beyond human means.

Radiohead were a band enduring mach-like pressure on a whirlwind tour, working through the rigmarole of rock and roll ascension for the chance at a moment’s rest. In the wake of OK Computer, Radiohead never had to match the pace of rock stardom, content with their own standard. Yorke found his own contentedness too, and his fear of cars — long a lyrical inclination — has never since reappeared. It’s a neurosis that evolved into an all-embracing condition, one which could diagnose not only the band’s struggle, but the world in which that struggle was fought. It’s a tale of transit, speed, and the sudden brake that tears you limb-by-limb.

In the 1990s, as Radiohead rose from alt-rock aside to art-rock essential, vehicles held a special place in Thom Yorke’s mind. His obsession, sketched through typically evasive interviews, is often put to a general angst. “I'm utterly obsessed by people dying in car accidents,” he told Ray Gun in 1998. “People will worry about smoking or they'll worry about fucking what's in the water or how much cholesterol, yet they'll get in the car everyday and drive to work,” he explained, musing on the everyday perils of commutes. “I can't not think about it, it absolutely does my head in.”

Yorke’s aversion first burst through on 1992’s Drill, the debut EP — and first commercial release — from the recently signed group. Their arrival was borne of grungy guitars and upbeat rock riffs, but “Stupid Car,” recorded earlier that same year, featured tender fingerpicking and a lonesome, spotlit croon.

I find it hard to drive your stupid car / I find it hard, ‘cause I never get that far…”

In this telling, the “stupid car” is rendered a vague metaphor. Lyrically light and delicately lovelorn, it paints platitudes about losing control — “you put my brain in overload, I can't change gear, I cannot see the road” — in broad strokes. Still, the image of “concrete eyes” lends a modern brutality, and the act of being “crushed” by a lover’s hands calls to mind the mangled wreck of a totaled car. There’s a malevolence to the mechanical allusion, the indifferent vehicle itself imbued with the cruel touch of a difficult lover.

Though Pablo Honey was less concerned with automotive imagery, the thread picked up again soon thereafter, scratched by their sophomore EP Itch. A comparative rarity released exclusively in Japan, it featured a live rendition of “Killer Cars,” a song ballied about during the Pablo Honey sessions. This time around, subtext is scarce. Yorke’s fear takes centre stage, simmering in the verses and bursting into a soaring, desperate chorus.

In the subsequent studio version, Jonny’s roaring guitar underpins Thom’s cavalcade of fatalistic fears — “What if these brakes just give in? What if they don't get outta the way? What if there's someone overtaking?” — paired with the paralysing thought that even dipping out for “a little drive” could be “the last time you see [him] alive.” In Yorke’s vision, the cars themselves are the killers: the foolhardy thrillseekers that speed by are merely the “they” that drive the “killer cars,” and on his own fear-stricken commute, he worries about what might happen “if the car loses control.” The car is in control, and no matter how hard he grips the wheel, there’s no way to wrest it back.

“This is a song about waking up one morning, convinced that, err, my partner had been killed in a car accident,” explained Thom before debuting the song at a 1993 gig in Tel Aviv. “You know, it's one of those dreams where you're totally convinced it's happened. This is all the cheery guy I am.” It’s a story he often entertains, but the terror of “Killer Cars,” visceral and straightforward, seems more than just a bad dream. It’s an acute sore; a fascination so intense, it’s hard to believe it’s simply a persistent thought.

In a 1996 interview with Clare Kleinelder of Addicted To Noise, when asked about the recurring image, the singer pushed past the abstract. “Why are there so many references to cars? Well, I'll tell you why,” said Yorke, uncommonly open. “It's because when I was younger, my parents moved to this house, which was a long long way from Oxford, and I was just at the age where I wanted to go out the whole time. I used to have this one car, and I very nearly killed myself in it one morning, and gave my girlfriend at the time really bad whiplash in an accident. I was 17. Hadn't slept the night before.”

That’s a story, at least in part, about fearlessness. Yorke, on an autopilot of sorts, unwittingly wagered his life — and the life of his then-girlfriend — on the tread of his tyres. It was only in the wake of the crash that concern begat obsession. “My dad bought me another car, a Morris Minor, you know, and when you drove around corners in it, the driver door used to fly open,” he said. “Um, and I'd only do 50 miles an hour, and on the road that went from my house to Oxford, there was fucking maniacs all the time, people who would drive 100 miles an hour to work, and I was in the Morris Minor, and it was like standing in the middle of the road with no protection at all. So I just gradually became emotionally tied up in this whole thing.”

The interview provided the only glimpse into his obsession, but it came with a sort of inner peace: by 1996, the literal dimensions of the car had been largely supplanted by what the vehicle represented. OK Computer opens with “Airbag,” an auto-accident tale that eschews tragedy for a messianic rebirth. “I was really frightened of cars back then, but ‘Airbag’ was almost the opposite of that,” said Yorke in a 2017 Rolling Stone piece. “If you get into a crash or a potentially disastrous situation and walk away, you feel a thousand times more alive regardless of what that is.” In focusing on the airbag itself, he plays against the sentiment of “Killer Cars,” hailing his technological salvation instead of the ever-present threat of death.

The car soon pushes past the extremes of life and death, functioning as a potent symbol of modern life: compartmentalized, individualistic, trapped within an oppressive routine. On “Subterranean Homesick Alien,” Yorke yearns for a closer encounter than his humdrum existence can provide, his alienation taking on a cosmic bent. “I wish that they'd swoop down in a country lane, late at night when I'm driving,” he croons, imagining the visitors whisking him to “their beautiful ship” and gifting him a new lease on life. This fanciful flight from modern neurosis — everyone, narrator included, is “uptight” — sees the narrator pulled from his car and brought back to life.

If this drive isn’t riddled with fear, it still speaks to a form of death. This “uptight” life, coursing through the record, is all but lifeless, defined by slogans, commutes, and cold steel. The aliens, pulling Yorke from his boxy car, “show [him] the world as [he’d] love to see it.” That’s from miles above, far from the minutiae that mars the everyday, where vistas stretch out to the horizon, mountains and rivers stressing the insignificance of the ant-like crowds below. The extraterrestrial abstraction was inspired by Close Encounters of the Third Kind, but the stifling limits of a sterile existence — joylessly rushing from job to job, performing a function — was inspired by the years Radiohead spent on the road.

“If you spend all your time traveling on airplanes or on buses or whatever, you’re bound to get this sense like in ‘Let Down,’” said Yorke of that tortured fan-favourite. The song came together on The Bends tour, with the band travelling from city to city playing a gruelling roster of nigh-identical shows. There’s acute anguish to images of “transport, motorways and tramlines, starting and then stopping,” calling to mind glassy-eyed commutes and day-to-day banality. “It’s the transit-zone feeling,” offered Jonny in 1997. “You’re in a space, you are collecting all these impressions, but it all seems so vacant. You don’t have control over the earth anymore. You feel very distant from all these thousands of people that are also walking there.”

Yorke and Radiohead, having spent almost six consecutive years either touring or recording, were traversing the world, seeing the sights and playing packed-out shows to eager fans. Cities and stages coalesced into a blur as torturous schedules made the most of the world’s hottest band. Yorke, Selway, O’Brien and the Greenwoods were casualties of their own ever-quickening success. The surreal dreamlike imagery of the “Karma Police” video, which features a panicked man pursued by a slow-moving car, speaks to both the relentless pace of modernity and the risk of being subsumed by it. The flammable finale, a triumphant act of revolution, might be the most optimistic image of the OK Computer era.

On “Electioneering” and “Climbing Up The Walls,” the record’s one-two of political furor and paranoid fear, Yorke’s interest in Chomsky comes to the fore. A detour from the subway stations and fast-tracked careers littered in the album’s sleeve, there are nonetheless allusions to the unyielding pressure of their day-to-day. The lyric “I trust I can rely on your vote,” key to “Electioneering,” emerged from a personal tour joke, where a worn-down Yorke, tired of hand-shaking his way across the United States, began slipping the phrase into those rote formal greetings. It got some laughs, mostly confused, largely far removed from the way it riffs on the commerce of those nebulous business interactions, now entrenched in the alienating means-to-an-end of modern ‘networking.’ The central refrain —“when I go forwards, you go backwards, and somewhere we will meet” — uses movement to expose the absurdity of vain politicians and their oxymoronic promises.

“No Surprises,” a hymn for the broken and resigned, was written on “a shitty bus journey.” Elaborating on the song’s most intriguing lyric — the uniquely dynamic“bring down the government / they don’t, they don’t speak for us” — Yorke recalled scrawling it on “a two-hour bus journey with a bunch of old-age pensioners in Britain. I don’t know why my car wasn’t working. It actually wasn’t a political thing at all. It was like, ‘Why have people like this been dropped? Why are we just left to rot? If this is a democracy then they should be helping us. Why aren’t they helping us?’”

Yorke’s sense of social angst, fused with the image of transit, became a preoccupation that bled from lyrical allusions into the band’s other creative expressions. In Dazed #39 from July 1997, Thom’s freeform introduction to his visual art project The White Chocolate Farm included the phrases “art is my car” and “a danger on the roads.” The cover of the No Surprises / Running From Demons EP was centred about a car, while the back sleeve features a motorway not unlike that on the famed OK Computer art. An accompanying CD booklet expounded on those themes, with Yorke and longtime Radiohead artist Stanley Donwood incorporating plane landing diagrams, fragments of airline safety information sheets, retrofuturistic helicopters, various jetliner profiles, and top-down illustrations of roadways and subway entrances. The terrific Airbag / How Am I Driving? EP speaks for itself.

“Lucky,” the record’s penultimate stroke, is similarly forthright with its vehicular mistrust. The cornerstone of OK Computer, “Lucky” revisits the oft-forgotten faith we place in our commutes —“I'm on a roll this time, I feel my luck could change” — and uses it as a broad romantic metaphor. The recurring image of superheroism confers that same thrill from “Airbag”; an aura of invulnerability in the wake of a near-death collision. That feels especially true when taken alongside the long-haul travels of the in-demand group. “They were actually on the road,” recalled producer Nigel Godrich of the recording. “I had only heard the song on a cassette. They showed up and we set up – they played it the night before onstage. So they’d worked it out and we just did it and I mixed it.” In a self-interview conducted for Dazed, Thom elaborated on “the edge” from the then-recently released single, quoting from Situationist philosopher Raoul Vaneigem:“'The history of our times calls to mind those Walt Disney characters who rush madly over the edge of a cliff without seeing it. The power of their imaginations keeps them suspended in mid-air, but as soon as they look down and see where they are, they fall.'"

“The Tourist,” Jonny’s powerhouse closer, confronts this high-speed culture with compassion. “He barks at no one else but me, like he’s seen a ghost,” sings Thom, the spooked dog a reflection on his ailing spirit. There’s a dialogue at play — “they ask me where the hell I'm going, at a thousand feet per second” — but the central refrain, “hey man, slow down,” is less a piece of advice and more an insular mantra. Yorke wails it, the guitars soar behind him, and the climactic moment of OK Computer turns out to be a desperate, introspective plea for patience. “I have certain days when my mind is going so fast that I just can’t control it, and it’s locked into that speed and it’s going to go forever,” admitted Thom to Mojo in 1997, “The Tourist is a sort of prayer to make it stop.”

The preoccupations of “The Tourist” were not unique. “Agitation. Panic. Paranoia... On trains, walking around, at home, everywhere,” said Yorke of the state in which he wrote. “The Bends was less like that… this has been much more about absorbing what’s going on around you when it’s most potent.” “Everything was about speed when I wrote those songs,” said Yorke in a retrospective with Rolling Stone. “I had a sense of looking out a window at things moving so fast I could barely see.” It’s a thought that evokes simple rule of physics: the faster you move, the greater the force when you pump the brakes — or hit the wall.

April 18, 1998. Radio City Music Hall. Radiohead, the biggest band in the world, stepped back on stage for their second encore. It would be the last breath of the two-year OK Computer tour, the final effort of their non-stop come up, and their last headline show of the ‘90s. “We’ve got one more song to play for you,” drawled Thom into the mic. “This is a new song.” He tossed an aside to the sound techs, strummed a few chords and, bathed in purple light, launched into “How to Disappear Completely.”

“That song is about the whole period of time that OK Computer was happening,” Yorke would tell Rolling Stone in 2000. “We did the Glastonbury Festival and this thing in Ireland.” The legendary set, coming just two weeks after the record released, very nearly wasn’t — Yorke had wanted to walk, and O’Brien had convinced him to stay. That climax, however, was just the beginning. “It was sheer blind terror,” he said to Rolling Stone in late ‘97. “My most distinctive memory of the whole year was the dream I had that night: I was running down the [River] Liffey, stark bullock naked, being pursued by a huge tidal wave.”

“Something snapped in me,” he recalled in the 2000 interview. “I just said, ‘That’s it. I can’t take it anymore.’ And more than a year later, we were still on the road. I hadn’t had time to address things. The lyrics came from something Michael Stipe said to me. I rang him and said, ‘I cannot cope with this.’ And he said, ‘Pull the shutters down and keep saying, ‘I’m not here, this is not happening.'” On the final night of that trying tour, Yorke crooned those words, tore his earpiece from his ear, flung it to the ground, and stepped back to the microphone: “Thanks a lot. We’re going home now. Thank you very much for coming.”

In Grant Gee’s excellent 1998 documentary Meeting People Is Easy, a beleaguered Thom slouches back on a shitty greenroom chair. Ed and Jonny sit across from him, and a handful of onlookers are scattered about the room. They’ve taken OK Computer to Japan, and the endless brunt of media relations — shown by Gee in a string of increasingly dour collages — is really taking a toll. “We’ve been running too long on bravado, believing how wonderful everyone tells us we are,” he begins. The tape cuts and Thom’s back again, visibly incensed. “Well, Jonny, last year, we were the most hyped band, we won all— we were number one on all the polls, and it’s bollocks, man! It’s bollocks!”

“Yeah a lot of that’s, yeah, yeah…,” says Jonny, trailing off. “Well of course it’s bollocks,” adds Ed, “but unfortunately, it’s the nature that if you make an album that…”. There are some dueling voices, but Jonny cuts through the noise: “I don’t see how that should change what we do.” Thom brings both his arms to the back of his head, restless, and runs his fingers through his hair. “Of course it fuckin’— it changes your mental, it changes how… you know, a lot of things have changed, and we… it’s just a headfuck! It’s a complete headfuck! Isn’t it?”

Yorke furrows his brow and blinks as the scene transitions, the refrain from “The Tourist” — “hey man, slow down” — fading in like well-timed advice. It’s less a piece of wisdom and more a burden he’s “bored” with; an obligation he entertains every show. It cuts to Yorke on stage, smiling and waving to a rapt crowd. They cheer, he removes the guitar, and the show is done. Moments later, he’s visibly struggling through more press engagements. Images of stop-start traffic flash on the screen, neon lights and washed-out streetlamps paving the way.

OK Computer was fashioned in the wake of tour exhaustion, but in propelling the group to new stratospheric heights, it became a vehicle for a far more intense disaffection. “I mean, from ’93 through to ’98 when we finished that tour we just had January of ’96 off,” said Ed in 2017. “That was the only time. We just kept doing it. Our manager said, ‘You can’t really stop until you’ve got to a place where you can take some time off and people aren’t going to forget you’.” In the pursuit of pop culture permanence, the road stretched longer, the fatigue set in faster, and the sheer energy surrounding Radiohead demanded more from a band that had little left to give. Years later, Yorke would recall “being sort of propelled into this weird state where people were projecting things onto me in a particular way. I didn’t have the right sort of support mechanisms to deal with it,” he continued, “so I internalized a lot of it.” A band like Radiohead seemed all but destined to return, but in the months that followed, the future seemed uncertain to the members themselves.

“I was a complete fucking mess,” said Yorke in a terrific Guardian interview from 2000. In the wake of OK Computer, he described himself as “really, really ill,” largely as a consequence of “just going a certain way for a long, long, long, long time, and not being able to stop or look back or consider where I was, at all. For, like, 10 years. And not being able to connect with anything. Basically becoming unhinged, in the best sense of the word. Completely unhinged." That perpetual motion bore down on his bandmates as well: in a Kid A profile from Q Magazine, Ed O’Brien remembered the OK Computer tour by the “huge fluctuations in emotion” that rendered him “a sort of non-human.”

That same piece saw Yorke’s post-tour struggles laid bare.“New Year's Eve '98 was one of the lowest points of my life,” said Yorke. “I felt like I was going fucking crazy. Every time I picked up a guitar I just got the horrors. I would start writing a song, stop after 16 bars, hide it away in a drawer, look at it again, tear it up, destroy it... I was sinking down and down.” As work began on their fourth record, stretches spent in Paris and Copenhagen were worse than fruitless, fostering a frustration that was only resolved down the line. “We did quite a lot of stuff and then spent a year hating it, and then ended up using bits of it, or even quite a lot of it,” said Jonny. “It was typical of us.”

Typical though those sessions were, Kid A marked a pivotal moment for Radiohead: they released no singles, filmed no music videos, sat for comparably few interviews, and posed for less promotional shoots. In place of the conventional media push was a forward-thinking internet effort in which the band disseminated short videos called “i-blips,” through both official sites and fan channels, complete with promotional soundbites of album tracks. Following the release, the band toured through the UK and Europe, performing to audiences of 10,000 in large logo-free tents. It was an approach devised in the wake of OK Computer, partially owing to their experiences, but also to the fruits of that harsh labor. Those years were time served; Radiohead’s hard-earned reputation gave them a creative control that had seemed so distant.

Their place in popular culture assured, the band were even discussing plans to eschew the traditional album cycle. “We'd really like to have more regular communications with people,” explained Colin Greenwood to Q Magazine, “as opposed to just having this massive dump every two-and-a-half years, and fanfares and clarion calls.” The next decade would see Radiohead at their most productive, releasing albums Amnesiac, Hail to the Thief, and In Rainbows — which came with a second disc — as well as live album I Might Be Wrong. Their pace quickened, but their pace slowed, fashioned about their own approaches to creativity and marketing. Long-haul tours stopped, daisy-chained album cycles ceased, and on the flipside of the millennium, a car was finally just a car.

The car — once a feared image of mortality, then a bleak vision of dehumanizing transit — was still running, but the band, with their hands on the wheel and their feet on the pedal, could finally exert control. After a decade-long trip on the road to rock stardom, and a few years recovering, it turns out that was enough.