The St. Ides of March

Hip-hop – like the nation from which it emerged – has long grappled with the push-and-pull of drug use, and while that’s recently meant pot, lean, molly and percs, it’s easy to forget about the moves that the alcohol industry made to capitalise on the culture.

Hip-hop is, at its core, countercultural.

It can be easy to lose sight of in a world brimming with Super Bowl appearances, crossover pop features and omnipresent Travis Scott ad-libs, but the culture that rose from the streets of the Bronx was steeped in innovative and unrestrained self-expression. An ever-expanding audience made hip-hop a vibrant scene, with newly-minted celebrities speaking truth to power and once-unlikely hits launching afrocentrism to mainstream radio, but with such success came consumerism.

It’s not at all surprising that malt liquor brands seized this expanding market: what is surprising is just how mercenary their approach was – and how successful their incursion proved.

A 1993 ‘It’s On (Dr. Dre) 187um Killa’ spread showing Eazy, 8 Ball in hand.

Admittedly, alcohol does have an edge: it’s legal, it’s socially accepted, and it’s an integral part of American identity. It makes sense that, like Matt McConaughey and his Lincoln, many emcees were drinking 40s long before anybody paid them to drink one. Eazy-E, an unlikely spokesperson, was amongst the earliest to invoke brand-name liquor on wax, his unsolicited shoutouts only deepening the brutal faux-realism of his raps. On 1987’s malt-titled “8 Ball,” included on the unofficial compilation N.W.A. and the Posse, he waxes poetic about his love of the Pabst-owned Olde English 800 malt liquor, spitting “Old East 800, yeah that’s my brand / Take it in a bottle 40, quart, or can...”

Fictional though his exploits may be, Eazy’s passion for malt liquor fits the character he was looking to portray. “Life And Death With the Gangs,” a 1987 TIME piece exploring the lifestyles of Los Angeles gang members, opens with a telling sentence: “Michael Hagan's idea of a good time is to guzzle a few bottles of Olde English "800" Malt Liquor and smoke PCP with his fellow gang members in the slums of south central Los Angeles.” If most would see that invocation as a negative association, the folks at Pabst saw it as an opportunity.

Their advertising conspicuously pivoted towards Hispanic and African-American audiences, and it didn’t take long for that audience to realise. In 1989, Pabst found themselves under fire from “22 public interest groups” who took issue with their aggressive and unabashed campaign. Lloyd Lopez, VP of the advertising firm behind Olde English, argued that a pivot away from sexual advertising in ‘88 showed their “sensitivity to the urban market,” though critics maintained that the high alcohol content of malt liquor, combined with the mass exposure, was aiming to exploit “the most vulnerable elements of society.”

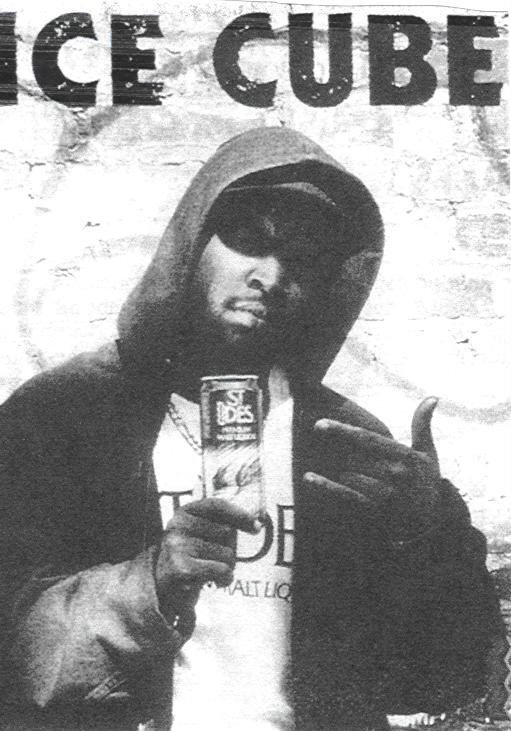

Cube, through his rapport with DJ Pooh, was amongst hip-hop’s first St. Ides promoters

It doesn’t take a cynic to know that when ethics comes up against a profit, many a company would rather be morally bankrupt. If Pabst set the scene, it was St. Ides who seized the moment, enlisting the help of DJ Pooh, a producer known for his work with King Tee, Del the Funky Homosapien and Ice Cube’s Lench Mob Records. In his piece for The Atlantic, Kyle Coward quotes onetime Source journalist Dan Charnas: “Musically, it was a landmark… I really believe it was the first time a brand turned over the creative keys to an artist to make commercials for them as they saw fit.”

Pooh wasn’t exactly a titanic name, but what he lacked in recognition, he made up for in associations. The first artists to jump at the opportunity were his closest collaborators, Ice Cube and King Tee, who sold the malt liquor with their macho masculinity and respected rhymes. In one of the earliest incarnations, Pooh and Tee take a trip to the liquor store in a branded car as the rhymes flow.

There’s certainly an art to the ad, which is steeped in hip-hop music video aesthetics and lighthearted rhyming fun, but that achievement is hard to remove from the blatant and unapologetic sell at the centre. If that last one was too subtle for you, the ads quickly paired Olde English disses with brags about the potency of the drink, a quality that soon became the focal point of their minority-angled advertising. Just take this particularly hard sell:

Now listen up close and set the 8 Ball aside

for a stronger malt liquor: it’s called St. Ides

I usually drink it when I’m out just clowning,

Me and the homeboys, you know, be like downing it

‘Cause it’s stronger but the taste is more smooth,

I grab a 40 when I want to act a fool

If they told you King Tee drinks 8 Ball, they lied,

I drink St. Ides”

– King Tee in a 1990 St. Ides Commercial

Cube infamously rhymed that you could “get your girl in the mood quicker, with St. Ides malt liquor,” the endorsement coming hot on the heels of his blockbuster solo debut, Amerikkka’s Most Wanted. It carried some real weight, and the emcee copped criticism and cash in not-so-equal measure.

Cube knocks back St. Ides in 1991’s ‘Boyz N The Hood’

The rock-centric SPIN Magazine included St. Ides Malt Liquor in ‘The Cold Rock Stuff,’ described as “a few of our favourite things,” in the January 1991 issue. “Malt liquor is a product normally targeted at the black community,” they opened, and though the folks at St. Ides were quick to paint Cube as only an infrequent drinker, they weren’t so coy about his entrepreneurship: “I can’t tell you how much he got,” they quipped, “but he’s talking of retiring at 25.”

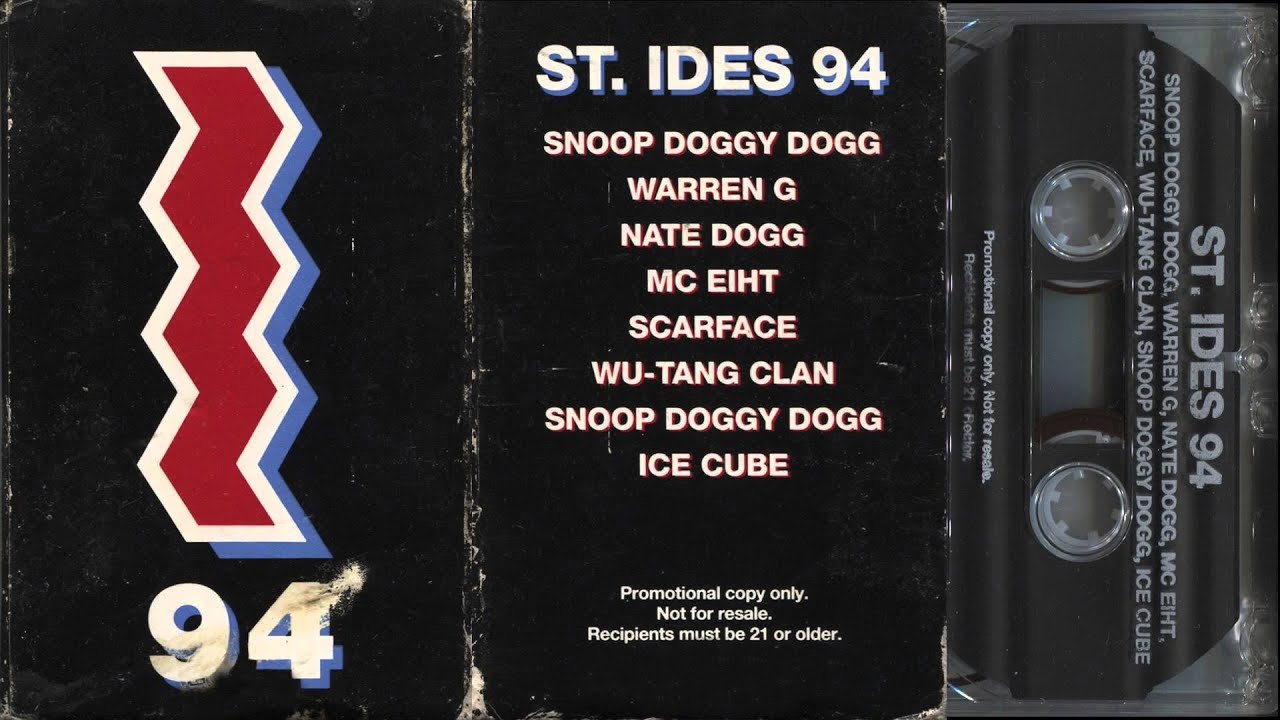

That’s hardly hyperbole given that, in ‘91, African-Americans bought “75 percent of all malt liquor.” A lucrative market made for lucrative endorsements, and DJ Pooh had hardly started: he had Cube rhyme alongside The Geto Boys in ‘92, an early moment of Southern hip-hop prominence, and tapped the West Coast leader to co-star with EPMD in their BB King-sampling TV spot. Tupac & Snoop linked up to hawk flavoured malt, and Snoop rode with Nate for yet another check. MC Eiht, untempted by the potential of Eiht-ball bars, jumped on the Ides in ‘94. Warren G flipped “What’s Next” into an Ides-infused jingle, and Cypress Hill even cheated on the sticky-icky with the malt liquor.

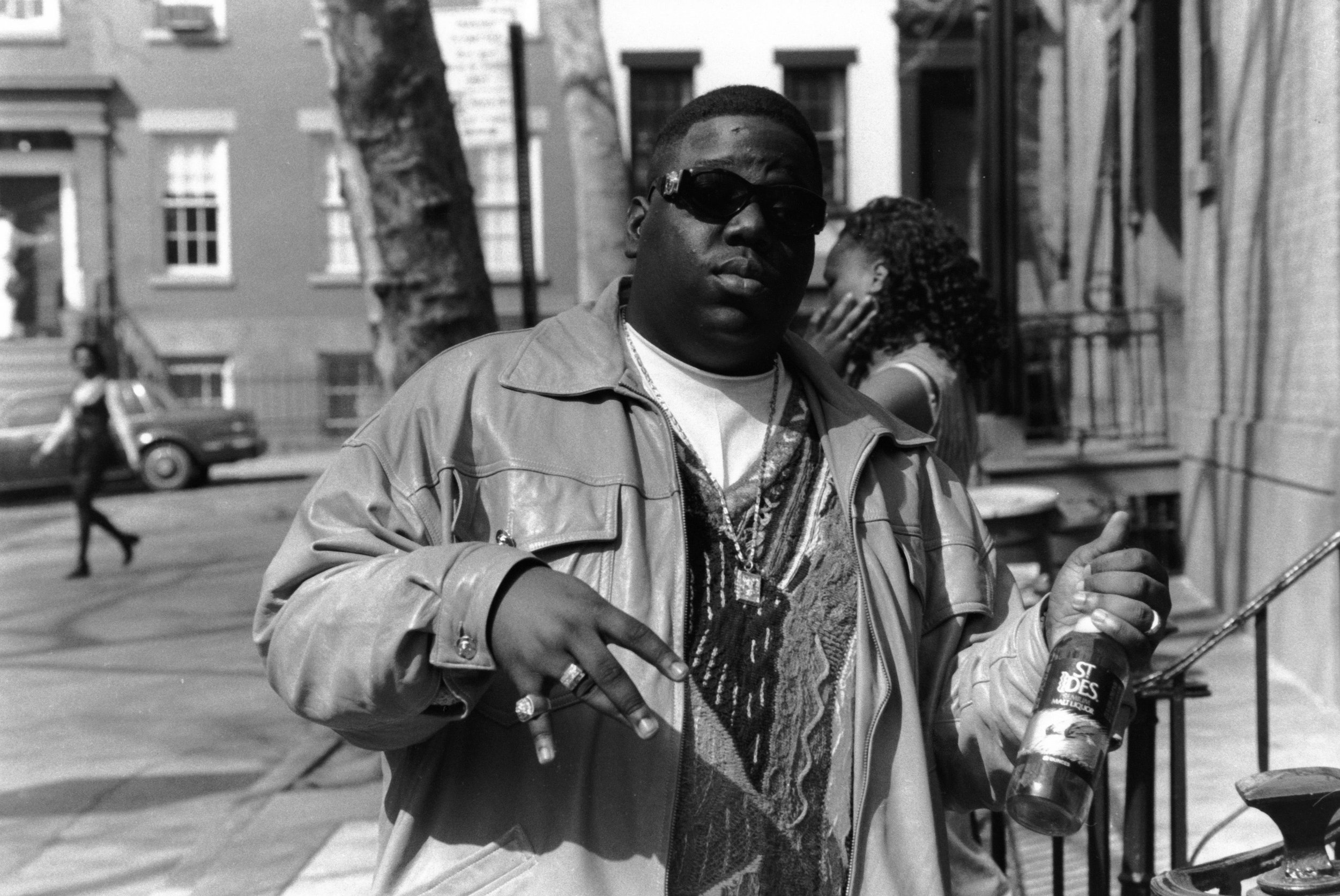

Pooh, who’d worked with LL Cool J in ‘87, also pushed into the East, recruiting the God emcee to spit some Ides-informed bars over “Don’t Sweat The Technique” and grabbing Biggie for a signature flow (over the eventual “New York, New York” beat) on how “no other beer feel better” than “the crooked letter.” He even convinced RZA to get the Wu-Tang Clan in on the project. You know what they say: cash rules, get the money.

It’s a diverse set of artists, but none come as a real shock. It was shocking, though, to hear Public Enemy’s Chuck D championing the drink he’d once said “deadens the brain,” but his voice appeared on a 1991 radio spot pushing the product. None were more shocked than Chuck himself, who’d only just released “1 Million Bottlebags,” a cut aimed squarely at the liquor executives targeting minority communities, and he sued McKenzie River Corporation – the name behind St. Ides – for $5 million.

It was pretty open-and-shut, with McKenzie sampling fragments of “Bring the Noise” – one of the group’s most militantly afrocentric anthems – to peddle drugs off the back of Chuck’s reputation. “Since as early as the beginning of 1991, in the neighbourhood where my son and I live, St. Ides Malt Liquor has been a pervasive presence,” wrote case witness Gretchen Gardner in a November 1993 Vibe piece. Her son, who’d counted Chuck as his “favourite hero,” had heartbrokenly considered him “a sell out and a traitor who was more concerned about money than principles” prior to the lawsuit. McKenzie settled “for a ‘substantial amount’ of money.”

‘St. Ides 94,’ the infamous jingle-featuring promo cassette

It didn’t make much difference. St. Ides managed to balance their ‘responsible’ initiatives, such as funding Cube’s post-Riots single, “Get The Fist,” and giving him the means for positive change, with their less earnest efforts, such as depicting rival gangbangers looting a crate of St. Ides in the wake of the Rodney King Riots, and running ads featuring Yo-Yo, then just 19-years-old. In 1992, following a lawsuit from the New York State Attorney-General, McKenzie River Co. paid a fifty-thousand dollar settlement and agreed to stop promoting the high alcohol content and appealing to underage drinkers. The advertisements kept coming – 1994 saw Snoop, Warren, Eiht and the Clan take the TV spots – and a St. Ides cassette was released, but tides were starting to change.

Kyle Coward of The Atlantic credits Diddy’s “ghetto fabulous” aesthetic, a cornerstone of the ascending Bad Boy Records, with pushing hip-hop from cheap malt liquor to more expensive brags. The earnest hip-hop flavour of the advertisements – lo-fi, grimy, familiar to fans – was undercut by an evolution in the culture, and emcees who’d held both influence and Ides were forced to choose. That newfound materialism spelled the end of St. Ides’ dominance, and the liquor itself was discontinued in ‘98.

In the September 1996 edition of Vibe Magazine, a column titled ‘Paid In Full’ looked back at the booming economy of rapper commercials. It threw a spotlight on Ice Cube, with Vibe arguing that the novel blend of hardcore emcee and faceless corporation “[couldn’t] justify pimping an addictive drug to black youth.” The same was said for Method Man, who took to promoting the troublingly juice-aligned St. Ides Special Brew in ‘96.

Unsurprisingly, Vibe made no mention of their own cosigns. That September issue alone lent full-page spreads to Absolut, Heineken, Bacardi, Dewars, Crown Royal, Budweiser, Hennessey, Seagrams and Miller Lite, brands whose pivot to hip-hop was marked by conspicuous slogans: “if he’s so tight, why doesn’t he have a record deal,” read one Heineken ad. Miller Lite ran with “I got my dreads, I got my threads, I got my beer.” Subtle.

Behold, the pervasiveness of corporate interests in hip-hop. That’s just how it goes, and whilst endorsements and deals aren’t inherently questionable, hip-hop’s love of liquor gave way for a slew of exploitation, defined by immoral – though not illegal – advertising tactics. That love persists today: Nas, Diddy and Jay have all dabbled in their harder liquors, the reputational opposite of street-ready malt liquor, riding endorsements and investments to further fortune.

That’s par for the course: though you might raise an eyebrow if a modern emcee prized liquor alone, you wouldn’t be all that surprised to see a rapper selling you something. Chance the Rapper is out here singing about Kit-Kats; Drake’s shilling for Apple; Kendrick’s plugging American Express; Vince Staples’ talking shit for Sprite, as is an ever-incredible Rakim; and even a deceased Tupac is reading “The Rose That Grew From Concrete” in a Powerade spot. As hip-hop has come to dominate the mainstream, so too have emcees, the onetime culture of countercultural firebrands now a potent consumerist tool. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with getting money – dollar dollar bill, y’all – but creatives should do so with vigilance, interrogating the way that corporate interests mobilise a passionate culture.

Snoop Dogg and the Crooked I, c. 1993

If anything, the relationship between hip-hop culture and predatory, white-owned enterprise is a lesson that’s all the more pressing in the face of the next great drug boom: marijuana. A nationwide reckoning of values ensues, and it won’t be long before emcees are championing wild strains with off-the-wall names in lifestyle magazines and after-dark TV spots. In an industry that’s shaping up to be less-than-representative, especially for those hit hardest by the last century of prohibition, it’s worth considering just what it is we’re being sold.

Exploitation can be insidious, and it’s often alluring and lucrative. It’s important to remember that whilst money makes for artistic achievements, production values, realised visions and cultural impact, the real cost is often far more than just the sum itself.